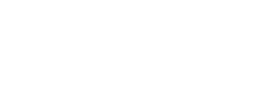

Calavera Tapatia, Manuel Manilla, no date

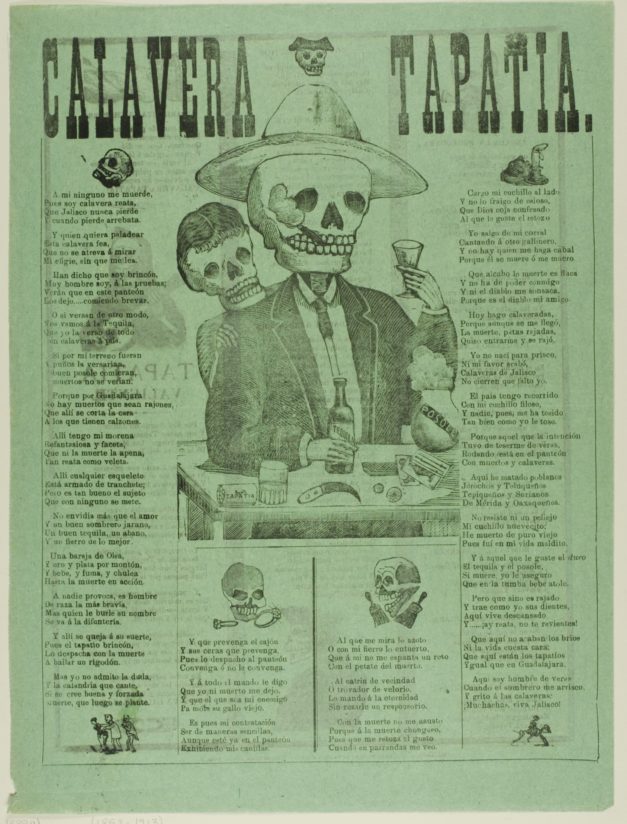

Glorious Success of Ponciano Díaz and His Brave Charros in the Bull Rings of Madrid, Manuel Manilla, 1889

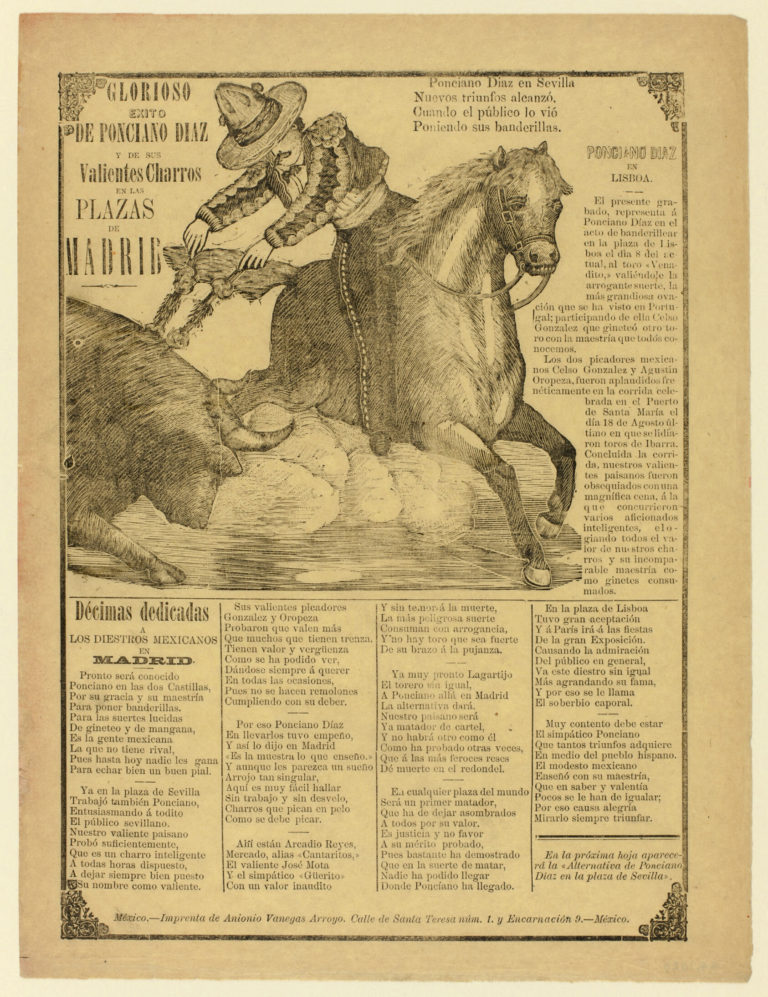

Assault on the Train from Cuernavaca by those execrable bandit Zapatistas, José Guadalupe Posada, printed 1910